The Ladder to Heaven

The Ladder to Heaven

By: Rabbi Ammiel Hirsch

Senior Rabbi, Stephen Wise Free SynagogueI was surprised to read that a sizeable majority of New Yorkers are opposed to the Islamic Community Center near Ground Zero.

We have changed since 9/11. We feel more afraid and more vulnerable. We are angrier and more resentful. We are less confident in ourselves. We are less optimistic than we were. We are less generous in practically every way – morally, politically and philanthropically.

We feel less resourceful and less competent. We have created banks too big to fail; dug oil wells to deep to fix; and have built weapons too powerful to use. Since 9/11 we have a general feeling that our performance has been sub-prime; that we can no longer dream big dreams, launch big projects or solve big problems.

We are angrier and more polarized than ever. Some bonds of trust Americans once shared have become junk bonds.

What is at stake in the debate surrounding the Islamic Center is more than the principle of religious freedom, although it is surely that too. What is at stake is more than the principle of political tolerance, although it is surely that too. What is at stake is more than a matter of geography – on what Manhattan block is it appropriate to construct an Islamic community center.

What is at stake is something even more fundamental: The dispute has exposed our weakened immune system; microbes of fear have invaded the lining of the American heart and are threatening to infect the body politic. We are on the verge of chronic heart disease. Like any patient with a chronic disease, we may be able to live fairly normally for even a long while, but sooner or later, it will debilitate us.

I miss those pre-9/11 days. I want our joy back. I want our confidence back. It seems to me that this is the key challenge for America. Talk about policies all you want. The urgency is to restore confidence in ourselves and faith in others.

Remember that day nine years ago when it all changed?

It was a glorious sunny day. You could see forever. The air was crystal clear. The cooling breezes of summer’s waning days had finally blown away the stifling humidity of August. This was New York at its finest. Manhattan had its groove back and was operating at maximum velocity again. The kids were in school. The adults were at work. Autumn was beckoning and spring was in our step.

On these rare days New Yorkers and New York become one; we feel the energy of the city surging through us. Life doesn’t get much better than this. To live in the greatest city in the world on one of its perfect days, is to live the American dream.

At mid morning the day ended. It became dark in the sunshine and difficult to see. A hideous black cloud spread over the city, hovering above us for days on end. It was hard to breathe. To breathe was to inhale our loved ones, our family, our friends and our neighbors whose flesh and bones were incinerated by the fire.

It was a day of contrasts: light and darkness; good and evil; humanity and barbarism; civilization and anarchy; heroism and cowardice; a cloudless azure sky and The Cloud.

For New Yorkers, perhaps most symbolic of all, testifying to everything good about humanity, were our firefighters; the people we rarely think about unless we need them. On that day, when heaven was falling and the earth’s foundations fled, they rushed up the stairs and on their shoulders held the sky suspended. They bore the desperate hopes and final confessions of so many human beings. The pillars of the earth held a while longer in deference to their valor.

We may be stingy with them now, a decade later, but many people are alive today because of the firefighters and other first-responders of New York City.

One person later testified that as he walked down the World Trade Center with a ninety year-old man he was assisting, he passed thirty to fifty firefighters heading up the stairs. “I don’t think any of them made it,” he said. “It was like a ladder to heaven.”

This is our task: to climb the ladder to heaven; to rise above the forces of brutality weighing us down and to imagine a better world, a world where heaven and earth kiss and where God and humans embrace:

And Jacob dreamt, and behold there was a ladder set on the ground and its top reached the sky and the angels of God were ascending and descending. God is in this place and that is the ladder to heaven.

Our task is to climb upwards, steadily improving and repairing our world until we break through the clouds of hate that hover over our lives and darken our horizons. How sweet is the light and how pleasing to the eyes to see the sun!

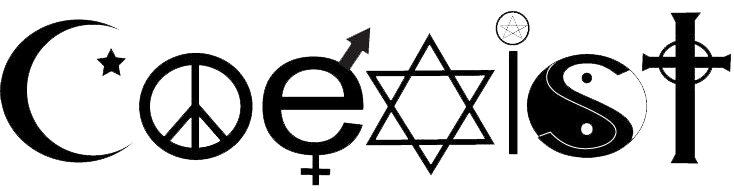

We need partners to construct the ladder. We cannot do it alone. We need people of different faiths to unite in common faith that we can make of this world a better place. Religion brings out the worst in all too many people. We must partner with religious leaders who can bring out the best in people.

It is for this reason that I am so eager to support those who are good. I am fully aware that no one is perfect. Those who are moderate; who seek a better world are on our side, even if we pray in different languages; even if we differ in tone, style or nuance; and even if we disagree on issues of substance.

All too many religious leaders justify murder, mayhem and destruction. I deeply yearn to support those who represent a different way. All too many religious leaders transform an act of violence into a noble jihad. They turn the world upside down through an unholy inversion of values: cruel is kind, killing is compassion and sin is salvation. Our highest aspirations are manipulated to excuse our basest impulses. “The Almighty wanted the baby killed. God decreed the collapse of the buildings.”

It is not difficult to claim divine sanction for murder. Even those who have a casual understanding of religion can cite chapter and verse to justify acts of violence. There are proof texts to support any position you choose to take. Religious people defended slavery for heaven’s sake. Those who opposed slavery cited verses from the same text.

In the end, it is not about citing chapter and verse; it is about establishing a mindset. At its best religion is a source of inspiration, not intimidation. At its best religion is about setting our hearts ablaze with a burning passion for the love of our neighbors, not setting holy books ablaze with a burning passion for the hate of our neighbors.

We must be on the side of those who seek to inspire, not intimidate. We must help them fight. We cannot fight in their stead because it is a civil war within their own community; but we can stand with them and give them the tools that will increase their chances of winning. We have a moral imperative and a strong self-interest to raise them up rather than tear them down. This is the greater good.

I want to be on the side of those who are for life. I do not want to be afraid; afraid that there are no good Muslims; afraid that every bastion of good – will be taken over by the forces of evil in some grand insidious plot to conquer America.

It is for this reason that I am so eager to find partners who are on our side; and it is for this reason that I have reached out to the organizers of the Islamic Center and offered them my support.

I do not expect them to agree with me on everything. I do not expect them to be more Catholic than the Pope or more Zionist than the Israeli prime minister. I will not put them through a forensic audit of political theory, probing their every statement in an effort to find some problematic association that I can tar them with. I will not argue from silence: because he has not commented on this or that outrage, by implication he is associated with that outrage.

I want to know: are you for life? We should support those who are for life.

If religion is for anything it is for life. The key insight of religion is the insistence upon the distinctiveness of the human creature. All were created by God. We alone were created in the image of God. Every religious principle flows from this axiom. If both you and I have been created in God’s image, we have equal sanctity, equal worth and equal dignity.

We have equal rights. If a church can be constructed on a Manhattan block then a synagogue can be constructed on the same block. And if a church and a synagogue can be constructed on a Manhattan block then a mosque can be constructed on the same block.

Reverence for life is religion’s primary preoccupation. It cannot be emphasized enough: the fundamental religious principle is the sanctity of human life. Every life is precious. Every life is sacred. “Whoever sheds blood destroys the image of God,” proclaimed the sage Akiva. The Talmud states that to save a person’s life is akin to saving the world entire, and to destroy a life is akin to destroying the world.

Islam has the same principle; I have heard imams quote it to me many times, without their even realizing that it was written in the Talmud half a millennium before the birth of Islam.

We must look for partners who believe in saving life, not destroying life. It is for this reason that I am so eager to support those who are on our side. I want to be on the side of those who believe that every life is precious. I want to support and encourage those who believe that saving a life is akin to saving the world, and to destroy a life is to destroy the world. This is the greater good.

Our age has produced wolves in sheep’s clothing. Savage and cunning, they cry “peace!” but let slip the dogs of war. They claim virtue but vice is their ally. They postulate goodness but are zealous for all that is vile.

From their dank caves and dark hideouts and from their gleaming sanctuaries and glistening shrines, religious extremists fling around the name of God as if the Divine were some appendage to their egotistical and perverted view of the world. Using the latest technology, the fruits of the labor of centuries of striving towards the light, they would take us back to the dark ages and wreak havoc and destruction on the most advanced and most humane civilizations in the history of the world.

Woe unto them who present darkness as light and light as darkness. What took centuries to build could be destroyed in one moment of murderous insanity. Millennia of human progress wiped away in the blink of an eye.

They consider themselves demigods freely invoking the name of the Holy One to justify horrendous crimes. They bestride the narrow world like modern day Goliaths, their swords dripping with blood. There is something primal and bestial about them. You see pictures of chopped-off heads, of burnings, bombings and knifings, and you ask yourself from what dark place did this emerge, what is the source of such fathomless depravity and bestial cruelty?

How did religion become the enemy of progress? How have we become agents of intolerance casually dishing out death and destruction? The name of God has been despoiled, dragged through the refuse of the world’s most fanatical deviants. For many today, God represents bigotry, oppression of women, violence and rage. How trippingly do the basest impulses of human beings form on the lips of those who swear loyalty to a higher cause! So-called holy men invoke heaven to perpetrate the most earthly crimes.

They are about rebellion, not religion. They are about superstition, not sanctity. By invoking divine authority they arrogate to themselves powers not theirs. They speak for themselves, not God. They act for themselves, not God. They represent themselves, not God.

It is their needs they pursue, not God’s needs. It is their flaws they exhibit, not God’s flaws. It is ambition disguising itself as a calling. Religion is the veneer. “To reign is worth ambition though in hell: Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.”

Our era has placed a sacred obligation on the forces and figures of religious moderation to speak up and build up. In an age when the world is saturated with religious extremism, upright religious leaders must uphold standards of decency and morality lest we call into question the validity of the religious enterprise itself.

And I want to stand with those who are moderate; who are upright; and who represent standards of decency and morality. I want to support those who are partners in progress, not the enemies of progress.

We should support those who seek to build up a new generation of moderate peace-loving people by building up moderate and peace-loving institutions. How else are we going to impact on people, if not through institutions and leaders devoted to moderation?

We cannot fight in their stead, but we can stand with those who are passionate for what is right in their bitter civil war against those who are passionate for what is wrong. This is the greater good.

It is for this reason that I offered the organizers of the Islamic Center my own services to help them form an interfaith advisory board of spiritual leaders, and I even offered to co-chair the Jewish part of this advisory board. I suggested to them that hundreds of rabbis would willingly and eagerly lend their support.

And I am challenging you: I would be prepared to bring before our synagogue’s board of trustees a resolution placing ourselves full-square behind the Islamic Community Center.

Because – with due respect to so many of my colleagues who have released sweet-sounding statements of brotherhood and dialogue and “Let’s solve this problem by sitting down together” – sentiments that I share and to which no reasonable person can object; still – with respect – it is not enough to release sweet-sounding words of peace.

The question before us now is: “do you support this center in this place organized by this Islamic community.” You need to take a stand, otherwise you are taking no stand. It is the task of leaders not only “to search for consensus, but to mold consensus.”

As Martin Luther King preached: “Our lives begin to end the day we become silent about things that matter;…The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

The problem with religion today is not that it permits killing. We do not have to resort to grand principles – common sense will do – to recognize the difference between murder and self-defense. The problem is in the misplaced emphasis on killing.

It seems that whenever we speak of religion today it is connected to aggression, murder, terrorism, jihad or extremism. Killing is a concession to a complex and baffling reality, not the ideal. The goal is stated by Isaiah: They shall beat their swords into plough-shares, their spears into pruning hooks. Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war no more.

I want to stand with those who speak of peace, not war; who emphasize virtue, not violence. All too many religious institutions are built and represented by people whose hands drip with blood. I want to stand with those of clean hands, who seek to build a House of Peace.

We are much too angry today. Anger dwells in the bosom of fools. We do not speak gently enough. We are not pleasant enough in our presentation of religion. Its ways are ways of pleasantness and all its paths are peace, say the Proverbs. Religious leaders should behave in such a manner that others will say of them: “See how pleasant are their ways!”

I want to stand with those who are pleasant. This is the greater good.

The problem today is not that religion encourages ritual. The problem is in the misplaced emphasis on ritual over ethical conduct. It seems that whenever we speak of religion prayer trumps piety, ceremony trumps sanctity, sacrilege trumps service and custom trumps common sense. The ritual police are on full alert, always ready to point out where we have missed a word here and skipped a prayer there.

I want to stand with those who do not see ritual as an end in itself but a means to an end. I want to stand with those who do not impose their ritual stringency on others; whose prayers are expressions of modesty and whose petitions are expressions of humility. This is the greater good.

The problem today is not that religion seeks truth. The problem is in the misplaced emphasis on truth over tolerance. We hear the claims of absolute truth and are driven to distraction by the arrogance and inanity of it all. In the heavens there are absolutes. On earth there are human beings, flawed and limited. How conceited must we be to present ourselves as the arbiters and dispensers of absolute truth and absolute justice?

In a remarkable interpretation of Abraham’s plea on behalf of the inhabitants of Sodom and Gomorrah – Shall the Judge of all the earth not do justice – Jewish sages placed in the mouth of Abraham the following challenge to God:

“If you want the world to endure there can be no absolute and strict justice. If you want absolute and strict justice the world cannot endure. You, God, would hold the cord by both ends, desiring both the world and absolute justice. Unless you relent a little the world cannot endure.”

Human life is incompatible with anything absolute. To insist on absolute truth and absolute justice is to destroy the world. Unless we relent a little the world cannot endure.

I want to stand with those who are pluralists; who realize that for the world to endure, we must live and let live, and who understand that “if we will not all live together as brothers, we will die together as fools” (Martin Luther King). This is the greater good.

The problem today is not that religion speaks of punishment. The problem is that we do not emphasize enough mercy and forgiveness:

Adonai, Adonai, el rachum ve’chanun, erech apaiyim ve’rav chessed ve’emet.

God, my God; compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in kindness and faithfulness, extending kindness to the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity, transgression and sin.

We forget that “mercy and truth are met together” in God. “The quality of mercy is not strained, it droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven. It is an attribute to God Himself, and earthly power doth then show likest God’s when mercy seasons justice.”

I want to stand with those who emphasize mercy. I want to stand with those who seek understanding and forgiveness. This is the greater good.

The problem today is not that religion emphasizes retribution. The problem is that we do not emphasize enough reconciliation. “Who is a hero,” ask the sages; “he who turns an enemy into a friend.”

I want to stand with those who seek to turn enemies into friends. I want to stand with those who emphasize reconciliation over retribution. This is the greater good.

I wish that we could reset the clock to September 10, 2001. I wish that it could all just go away; that our loved ones would be with us still; that we would have hope, joy and happiness in their embrace.

I know that there are some in the community of the bereaved who do not oppose the Islamic Center. But I also know that there are many good people, tolerant people, who lost loved ones on 9/11 and cry out in pain: “Our wounds have not healed; why there; why not build the Islamic Community Center a mile away?”

Those of us who escaped the death that visited your household on that day can never understand your pain. We can say nothing that will diminish your grief or replace what you lost. And so, I will not even try. All we can do is to hold your hand.

But I will say this to the rest of us – and I ask forgiveness if it is too painful for some to hear: We can also ask: “Why not there?” There are Muslims in that part of town. Should they be banished from that area forever?

In truth, the Cordoba Center organizers have not created this tension; they have merely brought to the surface the hidden tension that already exists. (MLK)

Some political activists are referring to the Islamic Center as a “Victory Mosque.” First, it is not a mosque; it will be a community center modeled off of our own JCC, with some space set aside for worship as in our own JCC and 92nd Street Y.

And second, if it is a victory; it is not a victory for radical Islam – that is what attacked us on 9/11. It would be a victory for religious tolerance and religious pluralism, moderation and the striving for peace.

That is my hope; that is my prayer; and I will devote myself to that end.

I regret not getting to know better my next door neighbor, Mario. We would meet casually from time to time in the elevator. He was thirty-two years old. He was gentle and kind, entirely different from the stereotypes of the so-called masters of the universe working on the top floors of the World Trade Center who presumably cared only about their portfolios.

He had an infectious smile, full of humanity. He had made it to the upper floors of American society but had not forgotten his humble origins. He was the first of his family to go to college.

I later read in the newspaper that Mario had planned on quitting in seven years so that he could use the money he had made to give back to society. We never really know these things about each other until it is too late. We discover them the day after, never the day before.

Two days after 9/11 I walked out of my apartment to find a man who was standing at the entrance to the building. I did not ask his name; I wish I had asked because I have thought about him for years. He appeared troubled. He had a vacant and distant look about him that was broken only when his son, a toddler in a stroller, mumbled some thoughts or gestured in some way.

I was not worried or perturbed. All of us were shocked and dazed. The city was filled with people who were walking around as if in a trance, looking for something or someone. So I figured that this man was probably one of those street walkers.

I asked him if he was looking for anyone. He said that he worked with Mario and was with him as they began walking down from the 84th floor of the World Trade Center. He had heard that Mario never came out and he felt a need to visit Mario’s apartment. He wanted to be around him; to feel his essence. He thought that he might run into Mario’s parents, and he wanted them to know how highly people regarded their son.

I have a feeling that somewhere within him he was hoping beyond hope that Mario had somehow survived and had simply returned home. I had that hope too; that Mario would just walk out the door, that it was all some misunderstanding; that he really was alive and, like so many of us, walked up Third Avenue at night and went to bed.

The man told me what had happened on that day. Mario was with him as they began walking down the burning building. The difference between death and life, between demise and survival was so trivial that to this day I am unable to fully comprehend the enormity of the banality.

Mario decided to stop at the restroom on the way down. He told his office mates to continue without him, and he would catch up with them momentarily. That was the difference between life and death; the extra time that it took Mario to visit the bathroom. I have never really overcome my sense of injury or offense. Why should the life of this gentle soul be snuffed out because of something as stupid as stopping for a minute or two?

What have these murders wrought? Mario would have had children. He would have brought happiness to all those fortunate enough to have crossed his way. Decades of life were ahead of him. The blood of the innocent cry out from Ground Zero: You have murdered this man; but not only that. You have murdered all of the lives that would have issued from this man. You have extinguished entire worlds. These voices cry out from the ground: “You are your brother’s keeper. What have you done?”

I showed Mario’s colleague the missing person flyer that his family had posted at the entrance to the building. He burst into tears. It was not a melancholy weeping. It came from a deeper place. It was inconsolable sadness. The man’s son, who looked to me to be about two years old, probably a bit confused and shaken at the sight of his weeping father, reached up from the stroller and grabbed his father’s arm.

And I remember thinking: here was the beginning of healing: Life and death. Optimism and despair; finality and a new beginning in the form of a small child’s outstretched little hand. We will survive. Life will go on. We will rebuild our shattered lives and our broken city.

I think about that boy now. He must be eleven years old already. I hope that he is living a good life. I hope that he is doing all of the things that a young boy should do. I hope that he is a happy boy, blissfully ignorant of the world’s unfairness and cruelty. There is plenty of time for that later.

Perhaps he has a brother or a sister conceived after 9/11. What a gift of fate. I feel like reaching out to the little boy and saying to him: No matter what; no matter how many spats you have; now matter how annoying you find your younger sibling, hold on tight and embrace your great good fortune. The difference between having a father and not having a father; between having a sibling and not having a sibling is the time it takes to stop at the restroom.

I hope that this boy grows up and lives a long, meaningful and useful life. I hope that he dedicates himself to something good. I hope that his father tells him about Mario; not to depress him, but to the contrary, to inspire him.

For in the end, Mario’s story is our story. It is a story of hope. It is a story of self-improvement and social repair. It is a story of those who refuse to descend into the pits of despair. It is a story of rebuilding and recommitting. It is a story of those who look for the good in people and who climb ever higher, striving towards the light.

How sweet is the light and pleasing to the eyes to see the sun!

It is a story of breaking out and breaking away, above the clouds that darken our lives, as we ascend the ladder to heaven.